Last year, England and Wales both introduced new building regulations that tightened the limiting air permeability for new buildings from 10 m3/hr.m2 to 8 m3/hr.m2, along with other key changes to how airtightness is regulated.

While these new targets are not especially onerous, they are just the start of a process that is likely to make standards even stricter. So how exactly have the regulations changed, what are the key facts that designers and contractors need to know, and how can you prepare for these changes? Read on to find out more.

What is Part L of the building regulations anyway?

In England, Wales and Scotland, as well as the Republic of Ireland, Part L is the section of the building regulations that covers the energy efficiency of buildings. It is designed to limit the amount of energy that buildings use, along with the associated carbon emissions.

Part L is accompanied by detailed guidance (known as Approved Document L in England and Wales) that provides technical advice on how to meet the regulations. Approved Document L sets limits for things like the U-values of walls, roofs and floors, the efficiency of heating and ventilation systems, and the airtightness of buildings, among many other factors.

How is Part L changing?

Back in 2019, the UK’s then chancellor Phillip Hammond said that the government intended to introduce a ‘Future Homes Standard’ to England by 2025, “so that new build homes are future-proofed with low carbon heating and world-leading levels of energy efficiency”. The UK has pledged to bring its overall carbon emission to net zero by 2050.

The government then announced that there would be an interim ‘uplift’ to the building regulations prior to the introduction of the full Future Homes Standard in 2025 (the Future Homes Standard was later renamed the Future Homes and Buildings standard, to reflect the fact that it applies to both dwellings and non-dwellings).

Wales has followed a similar path, and last year an uplift to Part L came into effect in both jurisdictions. (Guidance in Scotland and Northern Ireland is somewhat different, so will not be covered in this article).

In this blog post, we will specifically look at how regulations around airtightness have changed in the new version of Approved Document L for England and Wales, and we will also take a look at how the industry can adapt to tougher airtightness standards.

While Approved Document L sets out ‘limiting’ figures for air permeability and U-values, which are the absolute minimum standards for these elements, buildings must meet overall energy and carbon performance target as well, and reaching these usually means achieving better than the limiting values for at least some elements.

Overall, the new guidance in England requires a 31% reduction in calculated carbon emissions for new dwellings and a 27% reduction for non-dwellings compared to the previous regulations. In Wales, the reductions are 37% for dwellings and 28% for non-dwellings.

So how do recent changes to Part L effect airtightness?

In both England and Wales, the maximum permitted air permeability for a new dwelling has been reduced from 10 m3/hr.m2 to 8 m3/hr.m2 @50Pa. However, the ‘notational dwelling’ described in Part L, against which am actual building design is compared, has an air permeability of 5 m3/hr.m2. In Partel’s experience, 5 m3/hr.m2 is a more common worst case scenario in new builds in the UK.

The maximum air permeability for buildings other than dwellings has also been reduced from 10 m3/hr.m2 to 8 m3/hr.m2 in both jurisdictions.

Critics have argued that the figures could have been more ambitious. Indeed, figures from the UK’s Airtightness Testing and Measurement Association indicates that the average airtightness of a new dwelling in the UK was already at about 5 m3/hr.m2 as far back as 2016.

It is anticipated that both England and Wales will reduce the maximum air permeability, at least for new dwellings, to 5 m3/hr.m2 when introducing the next update to Part L in 2025.

Sample Testing

The other significant change with regards to airtightness in the new regulations is that every single new dwelling will now have to be tested for air permeability, whereas before it was possible to test just a sample of dwellings on multi-unit schemes.

Requirements for ventilation in an airtight home

Any update to the regulations surrounding airtightness also requires close attention to Part F of the building regulations, which in England and Wales, covers ventilation. This is because as dwellings get more airtight, it becomes more important to ensure they are properly ventilated through mechanical means.

In both England and Wales, Approved Document F now only provides guidance for so-called ‘natural ventilation’ (such as ‘hole-in-the-wall’ or trickle vents) in dwellings that are defined as ‘less airtight’. These are dwellings that have a design air permeability of 5 m3/hr.m2 or worse, or an as-built air permeability of 3 m3/hr.m2 or worse.

The implication is that natural ventilation by itself is not acceptable in more airtight dwellings, and that these should have a mechanical ventilation system such as continuous mechanical extract ventilation or heat recovery ventilation.

How do England and Wales compare with Ireland?

The Republic of Ireland is a few years ahead of both England and Wales in its journey towards net zero buildings, and it is interesting to compare how Ireland’s regulations have advanced, and how the average air permeability of dwellings there has progressed at the same time.

New regulations for dwellings, introduced in Ireland in 2019, tightened the maximum air permeability to 5 m3/hr.m2, down from 7 m3/hr.m2 in the previous version of the rules.

However, in reality designers and builders were already well ahead of these targets. In 2017, the average air permeability of new homes in Ireland was 3.66 m3/hr.m2 according to research carried out by Passive House Plus using SEAI’s National BER Research Tool. By 2021, that had further reduced to 2.55 m3/hr.m2.

In Ireland, Technical Guidance Document F only advises the use of natural ventilation in dwellings with an air permeability higher than 3 m3/hr.m2.

Adapting to the new targets

So how can designers and contractors in England and Wales adapt to the new targets? While 8 m3/hr.m2 is not an onerous figure, it’s important to remember that this is just an absolute maximum for air permeability. Because compliance with Part L in England and Wales is based on a building’s overall energy and carbon performance, going further than the backstop will make it easier for a building to comply (as well as delivering a higher performance building, when combined with proper ventilation).

How do you comply with Part L?

In both jurisdictions, Approved Document L contains a notional building specification against which a real building is compared to demonstrate compliance, and this notional building has an air permeability of 5 m3/hr.m2. The notional building is intended to show a typical specification that meets the regulations, so overall, 5 m3/hr.m2 is a much more sensible target than 8 m3/hr.m2.

Making a building airtight

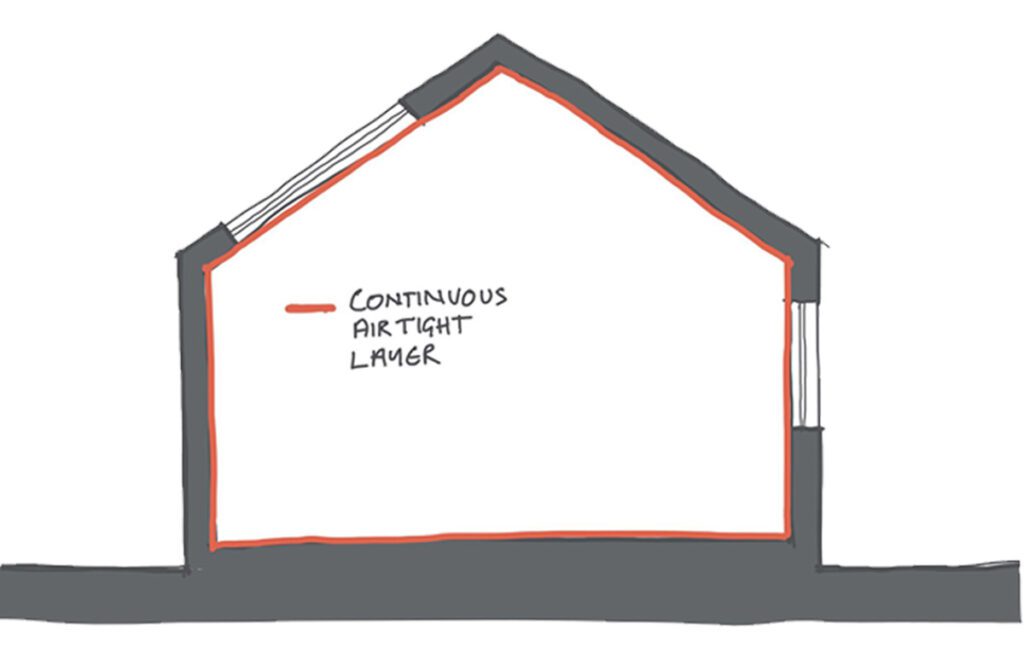

An airtight building is one that is highly draught-proofed, and airtightness is critical in high performance buildings for a variety of reasons. An airtight barrier prevents draughts and discomfort, reduces heat loss and noise infiltration, and stops the movement of moist air from the inside of a building into the structure, where it could cause dampness and mould.

Overall, a building’s air barrier consists of a combination of materials and installation processes that:

- Form a continuous airtightness layer in the floors, walls and roofing

- Seal the doors, windows and rooflights to the adjacent building envelope

- Link the junctions between walls and floor and between walls and the roof, including the perimeter of any intermediate floor

- Seal penetrations through the air barrier, including

- Incoming water, gas, oil, or district heating pipes

- Ventilation ducts

- Electric and broadband

- Chimneys and flues

Designing for airtightness

It’s tempting to think that airtightness is primarily the responsibility of those working on the building site, but it all starts with good design. Without a simple and understandable design that is feasible for the site team to deliver, it will be much harder to achieve a good standard of airtightness.

Some key principles for good airtight design include:

- Design the airtight barrier early in the design process — this will help to avoid complications later in the build

- Keep the building form simple with as few junctions as possible, as these are the points where air leakage is most likely to occur

- Keep drawings simple and understandable, with the airtightness layer clearly marked

- Make sure that the airtight layer can be visualised in 3D, as 2D drawings alone can be difficult to translate to site

- Minimise the number of points where the services cross the air barrier, such as by including a service cavity

- Ensure all parties on site understand the airtightness design and how it is to be delivered

Partel has published an excellent series of videos, entitled ‘Smart Airtightness Works’, which detail good practice to achieve airtightness.

The key airtight elements

It goes without saying that, in order to achieve an airtight building, the key elements of the construction — the roofs, walls, floor, windows and doors — must be airtight. This means that at least one element in the construction of each must be impermeable to air, and a continuous airtight layer must be formed.

Common airtight elements used in the building envelope include:

- Airtight membranes, such as Partel’s IZOPERM PLUS and VARA PLUS vapour control layers

- Proprietary airtight board

- Liquid airtight membranes, such as Partel’s VARA FLUID

- Precast or cast-in-situ concrete (such as for ICF construction)

- Wet plaster

- Damp proof membranes, typically used in ground floor construction

- Screed

How to prevent air leakage in buildings – sealing the airtight layer

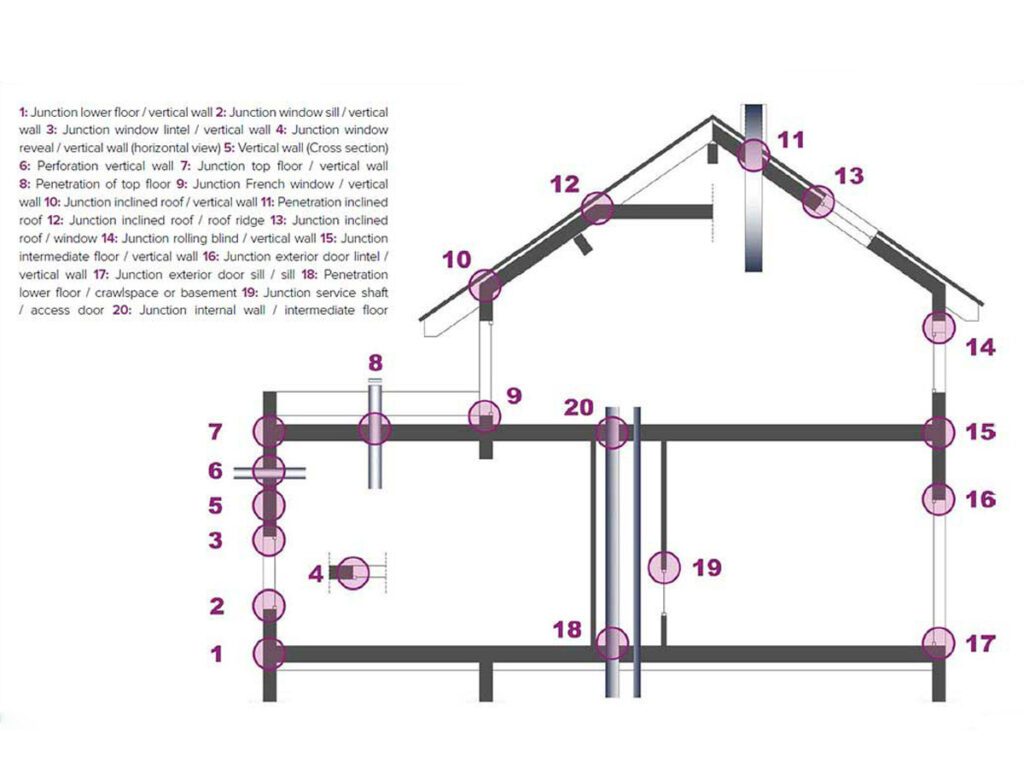

The final (and arguably the trickiest) step in securing a continuous air barrier is to make sure that the connections between construction elements, as well as any penetrations, are sealed to prevent air leakage through gaps and cracks in the fabric of a building. Typical locations that require attention include wall-to-roof and wall-to-floor junctions, window-to-wall and door-to-wall junctions, and service penetrations.

This is where good design becomes critical — to minimise the number of junctions and penetrations, and to make those that remain as simple as possible to seal. Partel supply a range of airtight tapes and grommets for ensuring a durable seal around penetrations and between all key construction elements.

In conclusion

The new airtightness targets in targets in England and Wales are just the start of a process that is likely to make standards even stricter. Partel have seen extremely high levels of airtightness in several projects, such as the Moorings passive house in Anglesey, Wales, which achieved an air permeance value of 0.6 m3/hr.m2, and the Willows, a certified Enerphit upgrade of a detached home in south Dublin which achieved an air permeance value of 0.98 m3/hr.m2. With a little preparation, and by applying good design, skilled workmanship and high quality airtight products, it is possible to meet and exceed the new airtight regulations in England and Wales — and to prepare for the continuing push towards airtight, net zero energy buildings.